On Saturday 7th June, 1913, two weeks before Ethel made

landfall in Adelaide 5 Charles Street

Further research turned up a letter to the Adelaide Register in July

1906, where the correspondent praised the influence of Mrs Moore and others

like her, in creating positive and intellectually nourishing environments for

the rising generation. She was then teaching at a school in Upper Sturt, a

suburb of south Adelaide Adelaide

Hospital

The domestic helpers’ hostel in Charles Street

The

interior architectural adornment of the place is in keeping with the pleasing

exterior view, so the house lends itself admirably to beautification. On many

of the door panels there are artistic hand-paintings. From the high balcony,

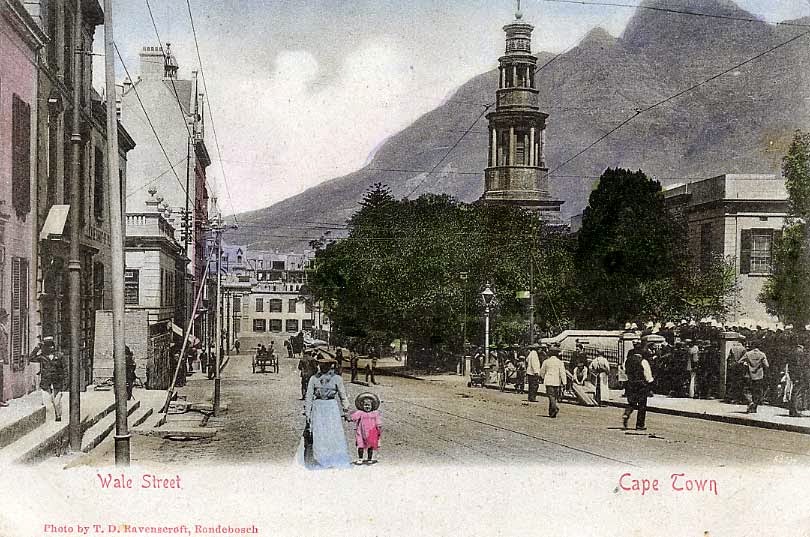

which faces Charles Street Mount

Lofty Ranges Australia

The Adelaide Daily Herald

article confirmed Bessie Moore’s bona

fides as a former State School headmistress, and that the hostel had been

at the Charles Street address for only seven or eight months:

Previous to this it had been

located at the Exhibition, [a complex of buildings erected in 1887 to

commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee] but it was decided to find a more

suitable place to carry on the work on a more comprehensive scale, and the

present building was rented by the Government for a period of three years, and

if this experiment is successful, it is probable that at the end of that term

the building will either be purchased or suitable premises erected to carry on

the work successfully.

Ethel had confided to her Journal that she was “leaving Home and Dear

Ones far behind, to commence life in a Strange Land

The home is a link in the

great chain of organisation of the immigration to Australia

And the above

extract seems to identify one of the mysterious contacts Ethel writes of in her

postcard correspondence to Minnie two years beforehand. From time to time other

accounts of the house in Charles

Street Adelaide

There is

a young lady, Miss Eaton, at the Immigration Home for Domestic Helpers in Charles Street , Norwood Adelaide Adelaide

Note from the

tone of this extract how the South Australians were looking for “industrious,

ladylike” girls to offer to their usually middle class clientele: they would

not have wanted women of doubtful morals in any way. Of course, the authorities

could not completely be sure of the girls’ backgrounds, but much care was taken

to cultivate and maintain a respectable ambience, so that prospective employers

could comfort themselves they were allowing ‘proper’ young ladies into their

households.

We work under splendid conditions, I think

because everyone is only too pleased to do everything possible to make our

attempts a success. We have a strong committee of ladies, representing every

religious denomination, with Mrs. Nutter Thomas as president, [Staffordshire-born

wife of the Bishop of Adelaide] and on the first evening of arrival they come

in to see the girls and find out which church they attend, and so forth. Then

when the girls find situations they find her church and write to the ministers,

and perhaps put her in the care of other church friends, and so give her an

atmosphere of friendliness and welcome in her new sphere. Every Tuesday evening

Miss Boyer, B.A., gives us a talk on literature and books, on Wednesday we have

a dressmaking class, and on Fridays a musical evening. [Adelaide

Curiously, the

article from which this last extract is taken, Our Adelaide

One very sensible thing I was quite glad to

hear about – the girls are allowed and encouraged to bring friends of the

opposite sex to spend afternoons or evenings at the home. They gladly avail

themselves of this privilege, and spend the evening playing games or chatting

over the fire. There is little need to enlarge on the value of this.

This would seem

to have been designed to stop the girls from venturing out alone of an evening,

and to cater for the natural urges of young people far away from familial

influence. Even more curious, however, is the conclusion of the article which

sees the worthy Mrs Moore confiding to the interviewer that she was:

a student of many occult sciences, deeply

interested in the great questions of the day, which no open mind can afford to

leave undiscussed with its fellows. As we turned over magazines and books

concerned with psychic matters and talked of experiences that transcend the common

daily round, we drifted far away from the solution of the domestic problem.

Perhaps those

sentiments merely reflected nothing more sinister than the turn-of-the-century

fascination in western society with spiritualism. The movement appealed to women, and to those who supported

specific causes such as suffrage. But well-known figures, such as the author

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, had also taken it up to console themselves in

bereavement. There was another surge in the popularity of spiritualism during

and after the approaching World War, of course. Anyhow, from these

accounts we can be fairly certain that Ethel met Mrs Bessie Moore, was welcomed

and advised by her, and was sent out to her first position.